A Brief History of Beer Gardens

As temperatures begin to rise, it’s time to begin thinking about one of the great pleasures of springtime: an afternoon sitting under the shade of a blossoming tree, stationed at a long table, hoisting a liter mug of beer. Maybe even playing a game of dominoes.

Yes, beer garden season has arrived. So let’s take the time to thank two groups of people — the Germans who invented lager, and the Germans who immigrated to the U.S. in the second half of the nineteenth century. If it weren’t for them, baseball would likely be our only excuse to sip suds in the sun.

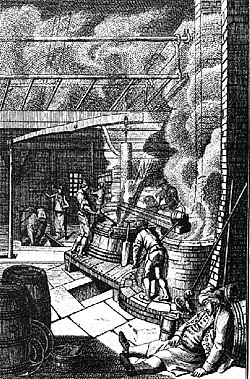

Unlike the ales that constituted all the world’s beer before the middle of the nineteenth century, the lager yeasts discovered in Bavaria at that time required a different type of fermentation. Ales — produced through the addition of top-fermenting yeast — ferment rapidly, at warm temperatures. Lagers, contrarily, depend on a slow, cool fermentation, ideally at temperatures between 45–56 degrees Fahrenheit. And after fermentation is complete, they need to be stored and aged for several months, at even cooler temperatures.

Unlike the ales that constituted all the world’s beer before the middle of the nineteenth century, the lager yeasts discovered in Bavaria at that time required a different type of fermentation. Ales — produced through the addition of top-fermenting yeast — ferment rapidly, at warm temperatures. Lagers, contrarily, depend on a slow, cool fermentation, ideally at temperatures between 45–56 degrees Fahrenheit. And after fermentation is complete, they need to be stored and aged for several months, at even cooler temperatures.

This was an era before refrigeration, however, so Bavarian brewers dug out large underground cellars for stashing the barrels while the beer “lagered.” To ensure fuller protection from the sun, they then scattered gravel over the ground and planted leafy chestnut and linden trees, which, as they grew, would provide ample shade from the sun.

Someone did the math. Shade, gravel, beer — all just off the banks of Munich’s Isar River, which provided an additional source of cooling for the beer. Put some tables and chairs outside, and start the taps. Beer garden culture was born.

In the U.S. to this point, our drinking culture came from the British Isles, where men would gather in inns or public houses to knock back their ales and spirits — generally far from the view of women and children. Meanwhile in Germany, Sundays (in particular) at the beer gardens had become a family affair.

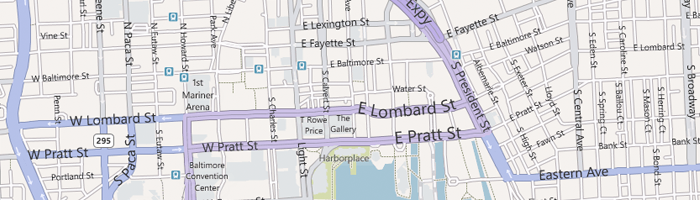

And when Germans started streaming across the Atlantic in the middle of the nineteenth century, they brought their beer gardens along with them, to cities like Milwaukee, Cincinnati, New York, and Baltimore. According to Andrew Barr, author of Drink: A Social History of America, while some of these American versions were actual gardens, others were simply indoor halls with long tables. Some had plants as a reminder of their outdoor origins. Occasionally, a large mural lined a wall, depicting a scene of natural splendor.

And when Germans started streaming across the Atlantic in the middle of the nineteenth century, they brought their beer gardens along with them, to cities like Milwaukee, Cincinnati, New York, and Baltimore. According to Andrew Barr, author of Drink: A Social History of America, while some of these American versions were actual gardens, others were simply indoor halls with long tables. Some had plants as a reminder of their outdoor origins. Occasionally, a large mural lined a wall, depicting a scene of natural splendor.

But even without sunlight, these destinations offered more than just beer. Kitchens turned out old country fare like schnitzel and wursts. And there was plenty of other entertainment too. In her book America Walks into A Bar, a history of American public drinking, Christine Sismondo notes that many of these gardens hosted shooting galleries, bowling alleys, and live classical music. Some spots even charged admissions, for certain patrons would come simply for the tunes and the atmosphere but would abstain from the libations available.

For a sense of the classic, pre-prohibition era of American beer gardens, take a trip to Astoria, Queens to visit the Bohemian Hall and Beer Garden. The oldest beer garden in New York City, they’ve been pouring out beer inside and outside since 1910. The space is a notable inspiration to contemporary restaurateurs, such as Aaron McGovern and Jeepo Vorobjovas, who opened Washington, D.C.’s Biergarten Haus in 2010, and Philadelphia’s Stephen Starr, who launched Frankford Hall in 2011. There aren’t any beer barrels aging in the cellar here, but with gravel on the ground and linden trees arching their branches overhead, the spirit of Bavaria shows demonstrates its continued appeal. Prost!

Top photo via Flickr user A. Currell